by Lindsay Mix

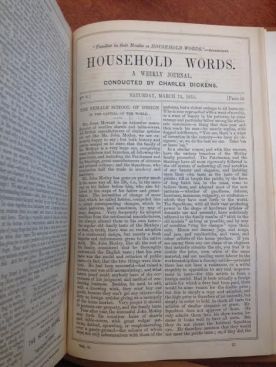

Charles Dickens’ 1850 piece “A Walk in a Workhouse” takes the reader on a tour through a Victorian workhouse. According to Dickens, these workhouses were filled with evil-looking young women, aged people, and depressed and subdued faces, and he describes the scene as “Pauperism, in a very weak and impotent condition” (116). In this piece, it is clear that Dickens finds the status of the lower class very problematic. He describes his walk through the workhouse using heart-wrenching descriptions of the old, and states that these people would be better off in jail. I find this very interesting in that literature of the time was concerned with this problem, showing that it was very relevant to people from all classes. This piece speaks to the progression that the majority of people thought should take place to better every class. I found a piece entitled “The Female School of Design” from an 1851 issue of Household Words that is comparable to Dickens’ piece in a number of ways. It was written just one year later, and shows how progression was still a major goal of many people. However, there are some differences between the two, the most significant being an emphasis on the increasing opportunities for women and the lower class in the work force in the second article.

“The Female School of Design” describes the emergence of design schools for both men and women in the Victorian era. Similarly to “A Walk in a Workhouse,” the author of this piece takes the reader on a tour of a female design school. Arguing that, while conditions were poor, these schools were still effective and important to maintain, the author notes, “Impossible as it was, from the state of the atmosphere, added to the extreme dirtiness of the windows, all crusted over, as they were, with London dust and smuts, to judge well of colours, in themselves, I could yet see that the best [candidates] had been selected, and the best harmonies employed” (579). While design schools were not created for the poor, they were accepted to study here. The author also discusses the commonality of girls becoming injured due to the dangerous environment. In addition to both pieces taking the reader on a tour, they take a similar stance on the issue by both offering a sympathetic glimpse of the challenging position lower class Victorian people were put in. These pieces are also similar in that they were both aimed at a similar audience, as they were published in Household Words just one year apart from each other.

An aspect of “The Female School of Design” that caught my attention was how women were becoming more involved in the work force and the trades in the Victorian era. The fact that this school was created specifically for women to learn trades and provide to household income shows great progression in Victorian culture. As the author says, “I leave London to-night by the express train, and shall present myself before my partners tomorrow morning in the warehouse, with uplifted hands and eyes; but I’m quite sure our firm will speedily avail itself of some of the designs of those industrious young ladies” (581). With this, the author is showing his interest in the schools, and the promise he believes they hold for young women’s continued education.

An aspect of “The Female School of Design” that caught my attention was how women were becoming more involved in the work force and the trades in the Victorian era. The fact that this school was created specifically for women to learn trades and provide to household income shows great progression in Victorian culture. As the author says, “I leave London to-night by the express train, and shall present myself before my partners tomorrow morning in the warehouse, with uplifted hands and eyes; but I’m quite sure our firm will speedily avail itself of some of the designs of those industrious young ladies” (581). With this, the author is showing his interest in the schools, and the promise he believes they hold for young women’s continued education.

While both Dickens’ “A Walk in a Workhouse” and “The Female School of Design” demonstrate similar views on the state of the lower class in Victorian culture, there are also certain differences between the two in terms of rhetoric. “The Female School of Design” author provides more personal insight than Dickens into the matter. Reflecting on a miscommunication in which the author thinks the school has been shut down, he notes,”I breathed again; my fears for the poor girls were allayed.” (578). This demonstrates his personal connection with the article and issue at hand.

Dickens’ voice is descriptive in “A Walk in a Workhouse,” but much less personal. For example, he discusses an old man who tells him if he could simply get out for some fresh air each day, he would be much healthier and happier. Dickens’ doesn’t voice opinion on the matter, but rather just explains the scene. “The Female School of Design” also has a much more positive ending that highlights the optimism and promise for the future of these schools and members of the lower class. Comparatively, Dickens’ piece leaves the reader feeling disturbed by the horrible conditions of the workhouse. Instead, this article ends in a much more uplifting way which is reflective of the change and activism in Victorian culture at the time, including closing the gap between classes and providing work opportunities for members of the lower class as well as women.

Not only were more job opportunities becoming available for women and members of the lower class, but conditions of workhouses were improving as well. In her article, “Changing interpretations of the workhouse?” Alannah Tomkins uses real-life experiences to show some workhouses were much more humane than others. She notes that “The workhouse or district school could be a refuge for children from a loveless, violent, or absent family” (31). While Dickens’ tour of the workhouse paints them as harsh and unlivable, later in the century conditions improved greatly, as Tomkins’ research shows. Workhouses became a home to many in need, so much that they were sometimes sad to leave (31).

Since the chosen pieces were written so close in time, there are many similarities among them. The fact that they were both published in Household Words shows they most likely had similar views and goals, and were aimed at the same audience. While “A Walk in a Workhouse” gives a more detailed description of life for the lower class, “The Female School of Design” reinforces the progression that was taking place and the importance many people in the Victorian era placed on taking care of all classes, as is seen through the author’s dismay when he thinks the school has closed, and his excitement once he sees the amazing work being created in the school. In addition to this, it explores the changing culture for women and this fascinating development in Victorian culture.

“The Female School of Design.” Household Words. 15 March 1851: 577-581. Print.

Dickens, Charles. “A Walk in a Workhouse.” The Broadview Anthology of Victorian Prose1832-1901 Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2012. Print.

Tomkins, Alannah. “Changing interpretations of the workhouse?” Teaching History 152 (2013): 30-31. Web.