Tags

Archbishop Whately, “Duty and Methods of Instructing”, Dissent, Freedom of Expression, Good Words, John Stuart Mill, nonconformity, On Liberty, opinions, religion, Victorian Culture and Thought

By Mary Luco

During the Victorian period, Christian faith spread across a variety of factions. There were divisions based on geography (Robbins 63), but there were also divisions based on nonconformist Dissent (85). Nonconformists pushed social boundaries and searched for liberty within what they viewed as an overbearing, subordinating church, tirelessly seeking to alter the establishment’s power (Briggs and Sellers 129). Faith was in a constant state of flux as people questioned religious doctrines, and many factions underwent reorganization, such as the Scottish Church (Robbins 63). Doubt extended from religion to other facets of Victorian life as well, further causing the populace to alter their world views as they gained new information—a noticeable political shift to the left occurred during this period (Reader 207). This tumultuous period provided a suitable setting in which writers such as John Stuart Mill and Archbishop Whately could disclose their thoughts on religious expression, agreeing that all individuals should be entitled to their own beliefs.

In the second chapter of On Liberty, John Stuart Mill explores the ideas of freedom of speech and thought in combination with how the existence of conflicting opinions can benefit individuals by providing a forum for discourse. This work was first published in 1859 as part of a longer piece that favours the dissemination of knowledge to all people and the opportunity for all opinions to be justified and challenged. He argues that all opinions should be presented to the public to determine their legitimacy, and that silencing opinions of any sort is negative to society as a whole. There are, nonetheless, some opinions that are correct, while others are incorrect. Sometimes, however, Mill finds that an opinion may fall into neither category; “instead of being one true and the other false, [the opinions] share the truth between them,” because the “received doctrine embodies only a part” (127) of the entire situation. In these instances, the value of the opinion exists in the compromise, and in proving knowledge for collective society, rather than just the individual. Mill’s discourse is later echoed by Archbishop Whatley’s investigation of religious teachings.

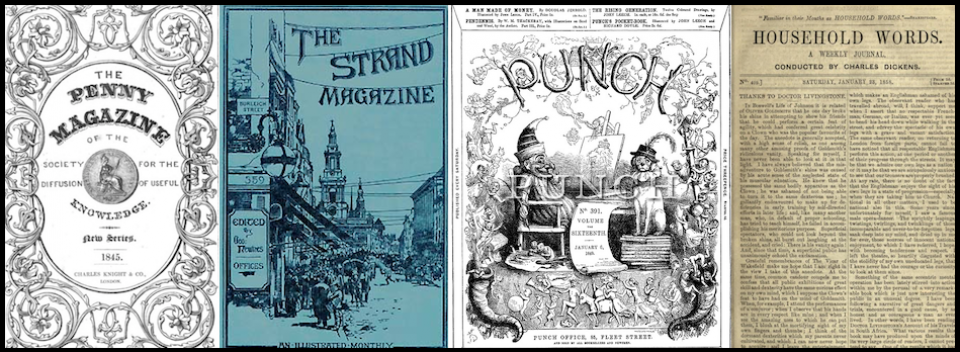

An article with a similar theme appears in Good Words in 1861, entitled “Duty and Method of Instructing” by Archbishop Whately, who discusses the best manner in which to guide people towards the truth. Good Words was published weekly between 1860 and 1906 and was a religious periodical suitable for the entire family to read each Sunday (“Good Words”). Edited by Norman MacLeod, this publication presented a variety of articles, illustrations, and serialized fiction to its readers. Archbishop Whately, a Protestant clergyman situated for much of his theological career in Dublin (“Archbishop Whately” 446), begins by describing a newspaper story he read in which, at a meeting of Agapemonists,1 “the speakers were cried down . . . as talking blasphemous nonsense” (Whately 133). The Agapemonists maintain that their leader, the so-called “Brother Prince,” was a religious incarnation, in much the same way that Jesus was claimed to be the son of the Christian God; both were subsequently decried for their beliefs. Whately then presents the argument that the only difference that exists between the case of Christ’s crucifixion and the denunciation of the Agapemonists is “the difference of evidence and no evidence” (134), and that devotion can be easily misdirected. He provides an example of misplaced faith in religious instructors who may select passages of scripture at random and then present them to their congregations without heeding the consequences of poorly-ordered speeches. Whately explains that this distortion is an instance of freedom of speech, but the content is taken out of context and therefore becomes liable to cause more harm than it would with its intended meaning.

An article with a similar theme appears in Good Words in 1861, entitled “Duty and Method of Instructing” by Archbishop Whately, who discusses the best manner in which to guide people towards the truth. Good Words was published weekly between 1860 and 1906 and was a religious periodical suitable for the entire family to read each Sunday (“Good Words”). Edited by Norman MacLeod, this publication presented a variety of articles, illustrations, and serialized fiction to its readers. Archbishop Whately, a Protestant clergyman situated for much of his theological career in Dublin (“Archbishop Whately” 446), begins by describing a newspaper story he read in which, at a meeting of Agapemonists,1 “the speakers were cried down . . . as talking blasphemous nonsense” (Whately 133). The Agapemonists maintain that their leader, the so-called “Brother Prince,” was a religious incarnation, in much the same way that Jesus was claimed to be the son of the Christian God; both were subsequently decried for their beliefs. Whately then presents the argument that the only difference that exists between the case of Christ’s crucifixion and the denunciation of the Agapemonists is “the difference of evidence and no evidence” (134), and that devotion can be easily misdirected. He provides an example of misplaced faith in religious instructors who may select passages of scripture at random and then present them to their congregations without heeding the consequences of poorly-ordered speeches. Whately explains that this distortion is an instance of freedom of speech, but the content is taken out of context and therefore becomes liable to cause more harm than it would with its intended meaning.

Whatley’s use of metaphorical analogies instills a poetic quality into his writing; he compares an individual’s beliefs to a ship that may be left to drift without “the compass and rudder” and “as easily as not run upon the rocks” (134), providing an example of how rhetorical imagery can enliven an argument. He furthermore alludes to the “Laputan” method of designing clothing without taking actual measurements from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (136), referencing an unconventional procedure that gives unsatisfactory results in conjunction with the ridiculousness of the scenario to demonstrate that his argument has universal applications and that some opinions do not make sense. Like the Laputans, ordinary people commonly hold misguided beliefs, and it is the duty of open-minded individuals to demonstrate a proper manner of thought. The most effective way of altering an incorrect opinion, Whately suggests, is “by proceeding on the principle of the inclined plane” (136), whereby an individual is gradually introduced to the correct concept and gently guided to realize that his or her belief was previously misinformed. Communication is a critical component of the discourse, and Whately stresses that one “must hear [individuals], as well as speak to them, so as to ascertain what are their difficulties, prejudices, and habits of thought, and what they have understood or mistaken in what was said to them” (136), and that it is only through such consideration that a correct concept can be instilled in the minds of lower-class people.

There are many parallels between the excerpt from Mill’s work and Archbishop Whately’s discussion of differences in viewing religion. The most unifying and notable example is the reference to Jesus Christ’s divinity, where in both instances he is described by his contemporaries as a “blasphemer” for claiming to be the son of God (Mill 126, Whately 133). Additionally, in much the way that Mill considers opinions to be either “false . . . or true” (127), Whately posits that there are both “rightly and wrongly directed devotion” (134), revealing a comparable stance on the underlying correctness of beliefs. The two authors also write with similar tones and objectives, each attempting to persuade his target audience that it is acceptable to hold resistant viewpoints as long as they are willing to accept and grow from criticism. There is also a shared emphasis on “encourag[ing individuals] to open their minds” (Whately 136), which presents a similar perspective to the thought that “there is always hope when people are forced to listen to both sides” of an argument (Mill 131), suggesting that openness is critical to the attainment of truth. Whately and Mill also discuss “morality” in regards to Christianity and determine that it is inherent in culture (Mill 129, Whately 134). Although Whately explores freedom of thought from a highly theological viewpoint while Mill focuses on the philosophical and social implications, the two pieces touch the same issue with the same convictions. Such a convergence of opinions not only demonstrates the similar perspectives of two different authors during the Victorian period, but it also provides an apt example of how opinions may differ slightly, yet still hold the same fundamental values.

Note

- More information on the Agapemonists, or Agapemonites, can be found on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agapemonites

Works Cited

“Archbishop Whately.” The Reader 17 Oct. 1863. British Periodicals, n.d. 446. Web. 22 Jan. 2014.

“Good Words.” The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900. Victorian Periodicals, n.d. Web. 20 Jan. 2014.

“Liberty or Equality?” Victorian Nonconformity. Ed. John Briggs and Ian Sellers. London: Edward Arnold Ltd. 1973. Print.

Mill, John Stuart. “Chapter 2: Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion.” On Liberty. The Broadview Anthology of Victorian Prose, 1832-1901. Ed. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge. Petersborough: Broadview P, 2012. 122-131. Print.

Reader, William Joseph. Victorian England. 2nd ed. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1973. Print.

Robbins, Keith. Nineteenth-Century Britain: England, Scotland, and Wales: The Making of a Nation. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

Whately, Richard. “Duty and Methods of Instructing.” Good Words Dec. 1861: 133-136. Print.