Tags

Childhood, Dressmaker, Girls, Labour, London, Mayhew, Poor, Punch, Victorian era, Working Class, Youth

Children of the nineteenth century in Britain were perceived to be the innocent, blank slate, idyllic creatures from the mind of Jean Jacques Rousseau (Bertram 5); however, many writers, reformers, and publishers were looking to expose the reality of childhood (Vlock). Henry Mayhew, a leftwing reformist, embraced this undertaking, showing what the children of Britain were really experiencing. Published originally in the Morning Chronicle, Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor was aimed at the middle class and looked to expose the realities of hardship and destitution of the lower class (Vlock). He took to the streets and wrote a total of 82 articles on “Those that Will Work, Those that Cannot Work, and Those that Will Not Work,” originally published between October 1849 and December 1850 (Mayhew). When these articles were put into volumes in 1851, the “Watercress Girl” remained an important one within the collection.

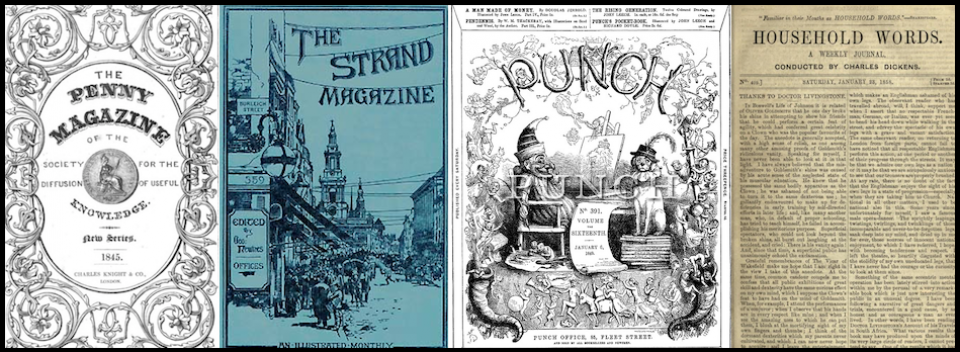

The “Watercress Girl” is Mayhew’s interaction with an eight-year old girl who sells watercress bundles on the London streets and defies the accepted, expected, and assumed vision of a young girl. Her story as a young girl who works is paralleled with an image of a girl who is worked to death at a dressmaker’s. This image, drawn by John Tenniel, was published in Punch, a periodical that Mayhew helped found in 1841 (“Punch”). Punch is the first periodical to use cartoons as political commentary; these were done in a sophisticated fashion and helped boost the popularity of the weekly periodical (“Cartoon;” “Punch”). This cartoon in particular works to destroy the assumed perception of poor and childhood being separate experiences. Mayhew and Tenniel are able to shock their middle class audiences with the actuality of youth as experienced by the concealed members of the poor through the use of measured language and presentation of the audience’s expectations juxtaposed with reality.

Madame La Modiste: “We would not have disappointed your ladyship, at any sacrifice, and the robe is finished a mervielle.”

The world these two girls exist in is both one of change and instability. When the Morning Chronicle first published “Watercress Girl,” the “Hungry Forties” was still affecting life as the Corn Laws were repealed only three years prior to this publication, and the Irish Potato Famine was still taking a toll. In 1847, the Ten Hours Factory Act lowered the number of hours women and children could work and was a time of many other articles and essays pushing for further reforms. Wood-pulp paper was in use, and in 1851 the Window Tax was repealed, these gave more diverse groups of people the opportunity to read. These changes were positive for social reformers like Mayhew, but were greeted with fearful sentiments and insecurity.

There remained the notion that the poor were the lazy men who would not work. In “The Haunted Lady,” the girl is quite clearly poor and worked very hard, but to no avail; this explains the dressmaker’s note on how she and her workers “would not have disappointed your ladyship, at any sacrifice.” She is implying that the girl’s death was an acceptable sacrifice for the creation of the dress, all of which is hidden from the upper class lady who can afford the financial cost of the dress, and will never know the cost of life (Tenniel 13). Furthermore, the speaker, the woman who is fitting the one in the dress has a certain level of grandeur about her, uses the French word “a merveille,” or wonder. This helps show the different class levels between the three women in the image; “a merveille” imposes a notion of class division and accentuates the juxtaposition of the girl who was worked to death and the two women who can afford to be alive. The dead girl is just the “ghost in the mirror,” intruding upon the dress in the reflection. The two are seen inside the mirror putting the final creation beside the hardship that went into it, a juxtaposition of hardship and creation (13). The image shows the shocking truth of labour, but hides it behind the glass so one must look for it, the same way it was hidden from the middle class, despite the effort of many to reveal them.

Similarly, the girl selling watercress knows the competitive and unforgiving nature of the street. She comments briefly on the anomaly of people showing her mercy or sympathy, “no people never pities… excepting one gentleman… but he gave me nothink—he only walked away” (Mayhew, “Watercress Girl” 120). Further, she notes that some saleswomen “are kind to us children” while others are “altogether spiteful,” despite all of them being in a similar situation there is some comradeship amongst the watercress sellers (120). She emphasizes that these women are not ladies, but the gentleman was a gentleman; she understands the function of hierarchy and can note the differences in appearance and what that means for their social classes. Mayhew uses her language to help the reader understand what the world looks like from the girl’s perspective. The use of the girl’s speech also puts the reader into Mayhew’s shoes with his implied questions helping to shatter the middle-class expectations. Although both the watercress girl and the ghost in the mirror served the middle-class, they were fundamentally invisible to them, requiring people like Mayhew to make them accessible.

The introductory portion of Mayhew’s article addresses the expectations of his own and the anticipated beliefs of the audience about children. He describes the girl and tells of how he hopes to communicate with her about childhood. The shock factor of the article and his revelations on the conditions of the poor relies upon this preamble. In order to help instigate social change, Mayhew tells of what people commonly believe childhood to be and through the use of the watercress girl’s voice he slowly destroys all these ideals of youth.

These young destitute women must work to survive and through that they break the perception of what girlhood means. The girl selling watercress “had entirely lost all childish ways,” been through the “bitterest struggles of life” (Mayhew, “Watercress Girl” 119), and she and other children are unable to play and have the experiences of childhood “’cos we’re thinking of our living” (120). The girl in Punch would have shared similar values, being worked so hard and malnourished that she died on the job. Their job acts as a guiding point for their lives. The watercress girl’s knowledge did not extend beyond the markets; she knew the monetary value of watercress and “for a penny [she] ought to have a full market hand” (121), while the girl in the image helped create the elegant dress that takes centre stage in the illustration. She is defined by her job, but it also is what hides her from the rest of the world. She is hidden in the mirror, the same way the girl selling watercress is hidden in the side streets of London; both work for the middle class while they are ignored and forgotten in return. Tenniel gives the reader a direct comparison of the sacrifice and recipient of that sacrifice to shock the reader in the same way Mayhew presents the standard middle-class expectations before shattering them with the reality of the watercress girl.

These two excerpts from periodicals show how Victorians were looking to change the perceived image of the poor. Both depictions of the young girls are done emphasizing the abnormality of who they are in comparison to the general expectations of who comprises the poor. Through the language and rhetoric chosen in both representations, the juxtaposition of the rich is shown; Mayhew’s gentleman and Tenniel’s woman wearing the dress stress the severity and hopelessness of impoverished young ladies.

Works Cited

Bertram, Christopher. “Jean Jacques Rousseau.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. Edward N. Zalta. Web. 27 Sept. 2010.

“Cartoon, n.” Oxford English Dictionary. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor: A Cyclopaedia of the Condition and Earnings of Those that Will Work, Those that Cannot Work, and Those that Will Not Work, Vol. 1. London: George Woodfall and Son, 1851. Google ebook. Web. 27 Nov. 2007.

—. “Watercress Girl.” The Broadview Anthology of Victorian Prose, 1832-1901. Eds. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2012. 119-21. Print.

“Punch.” Waterloo Dictionary of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900, 2nd series. Ed. John S. North. Waterloo: Waterloo Academic Press, 1976. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Tenniel, John. “The Haunted Lady, Or The Ghost in the Looking Glass.” Punch, or the London Charivari 45, 4 July 1863: 5. Print.

Vlock, Deborah. “Henry Mayhew.” Oxford Dictionary of National Bibliography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Thank you so much, this is very useful for my English Language exams in London.